I stood in line waiting to have my turn at the serving table.

My mind was in places, working to come up with appropriate illustrations for

the mid-morning teaching session after the break.

We were at one of the upscale hotels in Fort Portal, a town

situated approximately 300 kilometers west of Kampala the capital city of

Uganda. It is a beautiful town—cool weather, gently rolling hills and

easy-going people. From anywhere in the town, one can easily see the Rwenzori

mountain range in the distance and if you are not too pressed for time, a drive

to Bundibugyo 70 kilometers away further west will bring you to the foot of

these breathtaking ranges that stretch across the impressive distance of over 120

kilometers.

In front of me was one of the participants at the training

workshop we were conducting for a team of community leaders from the Bundibugyo

Area Development Program of World Vision Uganda. If I remembered correctly, his

name was Joseph. Always smartly dressed and well-spoken, he was no stranger to

me as we had interacted informally at previous workshops. As we neared the

table, he turned to me and started to make small talk, asking about how the

training sessions were progressing for me as a trainer. I indulged him for a

while and before long, it was our turn at the tea table.

There were three giant thermos flasks with labels that read “milk

tea”, “milk” and “hot water”. There was also a tribe of beverages to choose

from which included tea, drinking chocolate, instant coffee, soy coffee and

several others I would not be too bothered to sample. I had already decided

that I was going to make myself a cup of strong coffee to give me some kick and

help me combat the drowsiness that I was beginning to feel. Teaching can be a

draining job and I had been at it for four consecutive days.

As I was stirring my mug of coffee, Joseph was busy adding

spoonfuls of chocolate powder to his milk. Almost casually, he asked me a

question that caught me flat—footed and set me thinking in a whole new

direction. “Teacher, what is this?” he asked as he scooped more chocolate from

the tin labeled “Cadbury drinking chocolate”.

The question caught me off-guard mainly because it seemed to

me trivial and misplaced at that time in that hotel lobby. But as my tired brain

slowly digested it, its implication struck me like a blow and jolted me back to

life.

Basing on my secondary school geography/agricultural lessons

and from what I had read up on the subject here and there, I could clearly remember

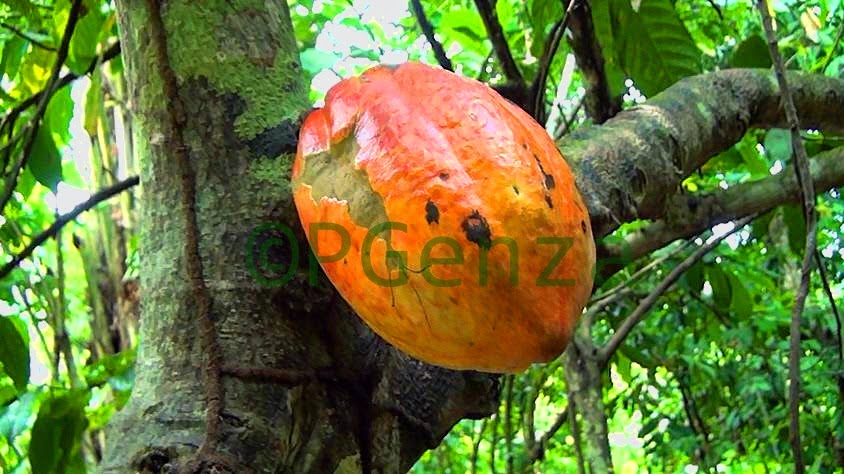

that chocolate is processed from the cocoa plant. The cocoa pods are harvested

from the cacao tree growing mainly in countries in the narrow belt 10ºN and

10ºS of the Equator, where the climate favors them to no end. The largest

producing countries of this much sought—after crop are Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana and

Indonesia.

West Africa and the Indian Ocean aside, I also knew that Joseph

hailed from the Bundibugyo region, an area famed for growing cocoa as its

number one cash crop. No homestead in this part of the country is complete

without numerous plants of the cacao tree strewn across its gardens. Trade in

cocoa has educated the children of Bundibugyo, built imposing mansions,

constructed schools, sparked endless feuds, been responsible for lavish

weddings, and made many well-intentioned folk polygamous.

It is that lucrative, and divisive.

I frowned in complete bewilderment at Joseph and at what I

thought was his simplistic question, and informed him that the dark brown

powder was called cocoa. His face quickly became a picture of complete shock as

his mind digested this latest piece of information. I think it was the word

“cocoa” that triggered him off. “You mean to say it is the same cocoa that we grow back at home?” I

replied in the affirmative and all he could do was look down and slowly shake

his head. He was clearly baffled by this new knowledge. It would seem that my

answer had caused him to experience a total paradigm shift.

The irony of this seemingly mundane episode could not be

lost on me. Here was this well-intentioned gentleman enjoying the luxury of a

beverage made from a crop he grew in his backyard, a crop I was certain he

interacted with on a daily basis from when he was a child, but

blissfully ignorant of how it was inseparably connected to the beverage he was now

enjoying from the comfort of this hotel lobby.

As I walked back to my seat thoughtfully sipping from the now-tepid mug of coffee,

I silently shook my head at the absurdity of the whole situation. I was certain

that from Joseph’s perspective prior to our little chat, the chocolate powder in these fancy tins was an

exotic beverage imported into the country for the luxurious indulgence of the

well-to-do who could afford to sleep in this hotel.

For the life of him, and except for that fateful question he

asked me innocently, he probably would never have been able to relate this

sweet brown powder to the golden—brown pods that hung from the cacao trees in

his gardens back at home, that the pods gave birth to the said powder.

Mother and Child!

And I thought, what a pity that from the perspective of Joseph,

the child was completely unknown to its mother. He grew the crop, harvested it

year in year out, sold it to some middle men who in turn sold it to some other higher-middle men, who then aided it on its elite journey to Cadbury’s state—of—the—art

factories in Singapore, and onward to Tasmania and Victoria (even Kenya and the

rest of the world) where it was processed, packed in those fancy, shiny tins

and eventually re-exported to Uganda.

Here it was distributed to various supermarket chains and up—market

hotels in places like Fort Portal so that during one random training seminar there, the likes of Joseph tasted the beverage with their milk and discovered for the first time that the tree which birthed this exotic powder grew in their plantations back home. Imagine the odds!

His could have been an isolated case of a child’s lack of

knowledge of its mother, and I honestly hoped it was but I knew in my heart

of hearts that I was wrong and that my hope was but a sham.

A few months later, I made a trip to the town of Bundibugyo.

Everywhere I passed, there were these cacao trees in full bloom, laden with

their unmistakable golden brown and maroon colored cocoa pods. At the Ntandi village cocoa cooperative union, I met a

gentleman who was weighing out a sack of dry cocoa beans, all nicely fermented and

ready to be sold to a waiting middle-man. I engaged him in conversation and asked him

what the beans were used for. He gave me a blank stare like I had requested him for directions to Mars. He blurted out “I do

not know”.

My heart silently wept at my government’s 30-year ineptitude

to build modern infrastructure for value-addition to agricultural produce, and by

extension, its active participation in the hypocrisy and sheer robbery of

capitalism.

Walking through a peaceful cacao plantation on an overcast

morning the next day, birds chirping cheerily in the sky, I stopped by a tree

with three beautiful maroon cocoa pods. Pointing my camera lens at them, they seemed

to look straight back and smile at me. With no premeditation, I smiled back, clicked

away some more and waved to them as I walked off thinking: Mothers deserve to know their

children, anything less is an affront to and a rape of their dignity.

|

| My Three Maroon Friends |

And you should stay true to your children son, paper and pen!

ReplyDeleteThank you sir. I have returned..

Delete